Edge of Care Cost Calculator: Change Project Report

Introduction

In 2017 a Research in Practice (RiP) Change Project, conducted with RiP Partners from 19 local authorities in England, explored the development of a tool for calculating the financial costs of delivering services for young people who are on the ‘edge of care’.

The Change Project method applies an action research approach to developing evidence-informed, practical resources by bringing together experts from across practice and research.

This project was a collaboration between RiP, North Yorkshire Children’s Services, and academics at the Centre for Child and Family Research (CCFR), Loughborough University (Lisa Holmes and Helen Trivedi, now based at the Rees Centre, University of Oxford).

Who this resource is aimed at

It is anticipated that the information generated by the resource will be of interest to service, finance and performance managers and those responsible for commissioning services, including Lead Members, Councillors and Directors of Children’s Services.

Given the multifaceted nature of a tool that utilises both financial and child-level data, it is anticipated that the various reports and analyses will provide information for both operational and strategic purposes.

About this report

Over the course of the project, local authority participants highlighted the diversity of approaches being taken to support young people deemed to be on the edge of care and informed our thinking on how a cost calculator tool might function effectively across such a variety of service activity. We have aimed to capture learning from the project and make recommendations, and have grouped our findings in the following sections:

- About the Change Project

- Defining the edge of care

- Local edge of care services

- Data for the edge of care

- The Edge of Care Cost Calculator tool

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the local authorities and the individual project participants for their invaluable contribution to this practice-research collaboration:

Blackpool; Cumbria; Dorset; Hampshire; Hertfordshire; Knowsley; Leeds; Lincolnshire; Manchester; Medway; Oldham; Oxfordshire; Rochdale; Somerset; Stockport; Swindon; Waltham Forest; Wigan; Wirral

About the Change Project

Background

In September 2014, North Yorkshire Children’s Services were awarded funding from the Department for Education’s (DfE) Wave One Innovation Programme. The award of £2.1 million was for the development of North Yorkshire’s ‘No Wrong Door’– an integrated service that aims to improve outcomes for young people aged 12 to 25 who are either in care, edging towards or on the edge of care. No Wrong Door was established to provide wrap-around care for young people from within a single service and develop consistent, supportive relationships.

From January 2015 to March 2017, Dr Lisa Holmes and a team from CCFR at Loughborough University led the DfE evaluation of the No Wrong Door model (Lushey et al, 2017). As part of the team’s evaluation methodology, it was recognised that there was a need to explore the true costs, and value, of delivering services to children and young people at the edge of care. The evaluation team began exploring the applicability of extending their existing Cost Calculator for Children’s Services (CCfCS) so that it could be used with data collected on the edge of care cohort, as well as looked after children. A pilot tool – the Cost Calculator for Edge of Care services (EoC CC) – enabled the evaluation team, in partnership with North Yorkshire, to better understand the true nature of support that young people were receiving and to analyse more effectively the value-for-money of No Wrong Door.

The EoC CC was conceptualised to support the longitudinal analysis of the needs, support, services and outcomes of children and young people on the edge of care. As with the original CCfCS, the underpinning methodology for the EoC CC is to take a ‘bottom-up’ approach to unit costing and to link these costs with data about the needs, circumstances and outcomes for children and young people. 1

The goal of the Change Project was to validate and expand on this work to enable the wider sector to benefit from the developments made in North Yorkshire. Ultimately, we intended to:

- Test and refine the functionality of the EoC CC and its areas of focus with a group of practice experts from a range of different local authorities.

- Use the information generated by this process to inform development of an updated practice-informed tool for the analysis of needs, costs and outcomes for young people at the edge of care.

Recruiting to the Change Project

Identifying and working effectively with young people before they enter care, and supporting successful reunifications after a period in care, offer clear benefits, such as improved outcomes for children and families, and (where appropriate) the avoidance or reduction of time in care for young people.

As the term suggests, edge of care services and activities often bridge service structures and operate at the intersection between targeted and statutory provision for children and families. Provision may be directed at different but overlapping cohorts such as:

- Young people and their families who are struggling to cope but whose circumstances do not necessarily ‘meet the threshold’ for statutory involvement.

- Targeted services are structured in a variety of ways around the country and the data collected are subject to a high degree of local variation. Referral processes, delivery models and monitoring systems are not uniform; these variations raise challenges in developing a tool with the capacity to gather comparable and/or linkable data to analyse the relationships between services, inputs and outcomes.

- Young people characterised as at the edge of care may well be involved with a number of different services.

- They may be involved with universal provision (in school or college, for instance), targeted provision (such as family support or adolescent mental health), services focused on specific issues (eg, youth offending), and statutory children and young people’s services. Bringing together data on these elements from different local agencies can be a challenge.

In order to scope further development of the North Yorkshire pilot tool to function effectively across this complex variety of activity, the Change Project brought together expertise in research, data, finance, and practice. Organisations from the RiP partnership network were invited to nominate participants to join a series of four meetings. Invitations were for groups of three individuals from each organisation:

- Head of service or senior manager with responsibility for edge of care services

- A performance and intelligence lead, such as an intelligence officer, business intelligence lead, senior data analyst, or similar

- A finance lead for Children’s Services.

The initial aim was to recruit three participants from eight or nine local authorities or children’s trusts (referred to throughout this document as ‘organisations’). However, the volume of applications greatly exceeded this target. In order to meet demand, we revised our plans and ran two concurrent project groups, one in the North and one in the South of England. In total, this enabled approximately 60 individuals from 19 local authorities to take part in the project.

The aim of the meeting cycle was to engage participating organisations in testing the conceptual framework and wider applicability of the pilot EoC CC. Key elements of the work included developing a shared understanding of edge of care services and the cohort of young people these were aimed at, and identifying the necessary data to explore the costs and outcomes associated with these.

A core issue quickly emerged around defining the ‘edges’ of care. The following section explores these issues, draws on the insights of those involved with the Change Project, and makes recommendations for future research and strategic thinking around edge of care services.

Defining the edge of care

Where are the edges?

While the term ‘edge of care’ has gained currency over recent years, the concept is defined in a variety of ways in practice, policy and research literature (eg, Ofsted, 2011; Institute of Public Care, 2015; Rees et al, 2017).

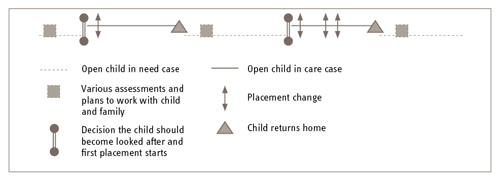

Change Project discussions underlined that in practice an ‘edge’ does not only describe young people who have not yet been in care (ie, those ‘edging’ towards it). Multiple edges may be visualised within the journeys a child or young person makes through early help, targeted family support, statutory child protection services, and in and out of the children in care system. Children and young people in care experience placement changes or breakdowns, family reunifications (which may also break down) and so may be considered on an edge of care at different points (see Figure 1).

These edges – and individual children and young people’s oscillation in and out of care – are, of course, functions of our system’s thresholds, service structures, statutory frameworks and legal orders. Evidence scopes and international research remind us that there are different types of response (see, for example, Bowyer and Wilkinson 2013; Wilkinson and Bowyer 2017), while innovation can move systems and practice into new configurations. ‘Rethinking support for adolescents in, or on the edge of care’ was one of two areas of focus for Wave One of the DfE’s Children’s Social Care Innovation Programme (2014 to 2017) in which nine projects explicitly targeted work with adolescents at the edge of care (see Rees et al, 2017).2

The negative consequences of placement instability and poorly supported family reunifications that subsequently break down have been well demonstrated in the literature (Farmer and Lutman, 2010; Wade et al, 2010), while others (eg, Holmes, 2014) have highlighted the rising financial costs of repeat returns to care and subsequent care placements. As such, both the moral and financial case for identifying and providing services to support this cohort are clear.

Definitions of edge of care

In this section, we describe several alternative definitions and the criteria they use to identify the edges of care.

Definition One: DfE Innovation Programme (Wave 1)

The Evaluation Coordinator for the first wave of the Innovation Programme worked with colleagues at the DfE to develop a definition of edge of care which broadly aligns with other definitions set out in recent years (Institute of Public Care, 2015). It was suggested that those on the edge of care are children and young people are who:

- A senior social worker believes will need to enter care within days or weeks as current levels of support are insufficient to safeguard them, while needs are escalating and/or family relationships or other issues are worsening.

- Are the subject of early-stage court proceedings and social workers are having to make decisions on whether sufficient change is possible to allow the child to safely remain at home.

- A senior social care manager has agreed should be accommodated if an alternative intervention or support package is not swiftly put in place, including those provided with respite care, or who have been accommodated in an emergency but where the aim is for them to be reunited with their family quickly with appropriate support.

- Cease to be looked after and return to their parents or wider family network, but who require further support to ensure they are safeguarded and do not re-enter care.

(Rees et al, 2017)

Definition Two: North Yorkshire

The three-part definition used by No Wrong Door (Lushey et al, 2017) in North Yorkshire is based broadly upon Definition One above, but with additional criteria and context from their service perspective:

1. Edge of Care: Those children and young people who are at imminent risk of becoming looked after:

- Families where there are significant child protection concerns, where child protection plans are in place and during the early stages of court proceedings, and where social workers are having to make decisions on whether sufficient change is possible to allow the child to remain at home.

- Young people who the appropriate social care manager has agreed should otherwise be accommodated but an alternative intervention or support package is put in place to safeguard them as a direct alternative to a long-term placement. This would include those provided with respite care or those who have been accommodated in an emergency but where the intervention will enable them to return to the family quickly, safely and with appropriate support.

- Children and young people who cease to be looked after and return to their parents or wider family network and where further support is needed to prevent re-entry to care and to ensure they are safeguarded.

- Children and young people who the appropriate social care manager considers will need to enter care imminently (within a matter of days or weeks) without significant support. This could be where needs are escalating – behaviour, family relationships or other problems are worsening and current levels of support are insufficient.

2. Edging to Care: Without an intervention package being put in place there is a strong likelihood of the case progressing to edge of care.

3. Placement Support – Outside of Family: Without an intervention over time the placement is highly likely to disrupt.

Definition Three: Wider literature

Across the wider literature, definitions of edge of care provide a broader view. Pulling together definitions from research and evidence scopes (Dixon and Biehal, 2007; Ofsted, 2011; Ward et al, 2014; Dixon et al, 2015; Institute of Public Care, 2015) the edge of care population may be defined as comprising those children or young people who match one or more of the following criteria:

- Is currently at high risk (professionally judged) of requiring protection from harm

- Has previously been considered for a care placement, which did not go ahead

- Has experienced multiple difficulties in their lives and shows signs of escalating need for support

- Has suffered abuse and/or neglect at some point in their life

- Has not been successfully supported by a service or multiple services, and has subsequently been moved around the Children’s Services system

- Is in an alternative to a long-term care placement with some sort of additional support

- Has very recently left care

- Has previously been in care and is still at risk of personal and accommodation instability.

Definition Four: Service-specific criteria

Working with Change Project participants raised the challenging issue that in local practice the definition in use may simply be ‘all children and young people who meet the criteria for and are being supported by our dedicated edge of care service’.

Given the variety and limited capacity (and in some areas, the complete absence) of named edge of care services, this pragmatic approach presents difficulties for ongoing research and development. Change Project participants consistently expressed the aspiration that a tool might provide analyses for benchmarking purposes, but ambiguous definitions and differing referral and eligibility criteria exacerbate the complexities of benchmarking and comparative analysis of outcomes.

Definitions: Summary

Across these multiple definitions differing approaches give weight to evidence gathered through two primary sources:

- Professional judgement: A practice-driven definition where service managers (or other appropriate professionals) identify young people as edge of care. This primarily applies to young people who are already on the cusp of being looked after or in the process of entering care, where professionals are able to assess cases closely and make decisions. This approach may help with the immediate provision of support but it is limited in its ability to enable earlier intervention and prevention of the need for care. Furthermore, it is subject to differences in individual professionals’ judgements and to human error.

- Service/child-level data: This broader definition considers multiple factors that may indicate a young person is at a higher risk of entering care. It might involve case history, current service provision, assessment data, and various other proxy indicators that evidence suggests are related to care entry.

This approach might support earlier intervention and meaningful preventative work with young people; however, it might also result in over-identification and present difficulties in directing support where it is most valuable. Furthermore, this approach does not take direct account of the expert, qualitative judgements of professionals, who will have a much deeper understanding of the cases that the data shows. It is also susceptible to human error, such as missing data and delays in updating records.

These approaches should be seen as complementary. Wherever organisations can supplement their service provision with additional insight from available data, there may be opportunities to intervene at an earlier stage with young people who will most benefit from access to services.

As such, a combination of definitions Two and Three above (the North Yorkshire definition supplemented by a research-driven definition of ‘edging to care’) might provide both flexibility to services in defining local cohorts and the structure necessary for further research and development in the field.

Children and young people at risk of entering care come to the attention of services for a variety of reasons and through a range of routes and agencies, and there is wide variation in the local offers available to them. This complexity and heterogeneity raise challenges in developing a coherent national research and commissioning agenda, as well as in the development of tools that may support analysis of these services. In the next section we discuss this variation in further detail, including the range of different ways in which data about practice activities and outcomes for young people are collected.

Local edge of care services

Variance in service provision

Diversity in service provision reflects factors such as local area demographics and demand, local area service development, reduction or consolidation over time, and the uneven distribution of innovation funding and activity in this field (Rees et al, 2017).

By bringing together strategic leaders from across 19 local authorities the Change Project aimed to gain greater clarity on how practice activity at the edge of care might be consistently defined, recorded and analysed.

Not all of the project group had a dedicated edge of care service and those that did used locally developed referral criteria and pathways, making it difficult to compare one service to another, much less to assess whether unit-level costs were comparable. Each service monitors performance in its own way using a combination of local authority systems and service-specific case management, resulting in a high degree of variation when it comes to edge of care data.

In the first Change Project meeting, participating authorities highlighted the differences in the types of services they were providing. Services could broadly be grouped under the following types:

- Services that work with adolescents who are deemed high risk for child sexual exploitation, involvement in crime, and/or at risk of harm.

- Services for families with multiple risk factors such as conflict, domestic violence, mental health challenges, and/ or substance misuse.

- Services for young people and their families following a previous care episode, and to prevent a future return to care.

- Services providing support to young people currently in care placements that are at risk of disruption.

The case study on the following page looks at two different edge of care services being provided by organisations that participated in the Change Project.

CASE STUDY: A comparison of two services

|

Service 1 Cohort: 70-100 cases Cohort description: Cases that are seen as high risk of entering care, but not those that might be exiting care. Service provision: Targeted work with young people and their families, focusing on support, resolution and multi-agency work. Data: Staff manually keep records of cases and enter data into a number of spreadsheets; however, no service activity, service-user data, or resources are entered into an integrated Management Information System. Other notes: The service has a dedicated budget for this provision which has grown over time. |

Service 2 Cohort: c. 170 cases Cohort description: Identified at a resource panel meeting of senior and key staff who review cases of concern brought to them by social work teams. Focus: Diverting cases from care and providing appropriate support. Service provision: If a case is assigned edge of care status then typically a family support worker will work with the family according to their needs. Data: Use a dashboard view of data about the cases. Other notes: The service has found that they keep numbers manageable by using this approach to referring cases. |

|---|

Outcomes for young people

This variance between areas in terms of services and cohorts presents difficulties in making a wider assessment of how effective services are at achieving their intended outcomes. Although financial calculations of services might focus on the cost of delivery and resources, unless these calculations are linked with the outcomes for the cohorts in receipt of the services, assessments of value are problematic.

So given the diversity of services, even within this sample of 19 organisations, there is a need not only for a common definition of edge of care, but also for a common framework of outcomes for this population.

At the top level, the general consensus across organisations is that the ultimate desired outcome for an edge of care service is a simple one:

- To prevent young people from entering or re-entering care (when it is not in their best interest to do so).

Alongside this primary outcome, however, are multiple other outcomes (identified throughout the project) which also aim to achieve this reduction in care placements. And in addition to contributing to a reduction in the need for episodes in care, these outcomes may themselves have wider societal benefits. These might include, for example:

- Reduction of exposure to domestic violence

- Reduction of alcohol and substance misuse (young person and/or family)

- Reduction in contextual risk of harm / abuse (eg, gang involvement, going missing, etc.)

- Reduction in offending and police involvement

- Improvements in physical and mental health

- Improvements in family relationships and communication

- Improvement of self-efficacy and coping with a crisis

- Improvement of educational outcomes for young people.

To summarise, edge of care practice encompasses a range of differing services working with a range of different cohorts of young people and seeking a range of different outcomes with young people and their families. A multi-area view of edge of care is impeded by a lack of uniformity in the available evidence. Just as services vary in this non-statutory setting, so too does the data collected in terms of people supported, services provided, outcomes achieved, and resources used. So although it is relatively easy for organisations to monitor and demonstrate changes in the number of placements over time (eg, via mandatory data returns from looked after children teams), the direct monitoring of edge of care services and outcomes poses a challenge.

Data for the edge of care

Child-level data at the edge of care

The variety in services and referral channels poses significant challenges for the development of generic tools for understanding needs, costs and outcomes at a strategic level. But without such tools, realistic comparison (both for internal organisation use and for benchmarking purposes) between costs, impacts and effectiveness of different approaches can be difficult.

In an analyst’s ideal scenario, there would be a single data record for each child that contains consistent data items (demographic information, services received, contact with multi-agency partners, changes in their circumstances over time, etc.). This single record would be uniform across all areas and would travel with the young person if they moved geographically or between services.

The single record would give a simple (two-dimensional) picture of that person’s life. When analysed with similar records for children across the country, it would provide practice leaders, analysts, commissioners and researchers with a starting point both to examine the complex interactions between services and outcomes, and to apply economic models to better understand (for example) the true costs of services.

Case study: Data-sharing in North Yorkshire to provide the best support to young people

When No Wrong Door was operationalised, it was quickly established that not all the necessary data items relating to needs, support, services and outcomes were routinely recorded or extractable from the case management system.

Therefore, No Wrong Door, in conjunction with the Centre for Child and Family Research at Loughborough University, who were evaluating the service, designed a child-level data tracker that was used in addition to the case management system.

This tracker was invaluable for the evaluation process and showed the impact of the specialist roles and the portfolio leads from the No Wrong Door service. As the tracker has developed, the team at No Wrong Door and North Yorkshire have looked at ways to ensure that the tracker and case management system are communicating, and that data are being updated in parallel.

This work is part of a larger process developed by No Wrong Door – the RAISE (Risk Analysis Intervention Solution Evaluation) process. This is a multi-agency, intelligence-led approach to assessing how best to support young people with the most complex needs and reduce their risk of harm. RAISE is also being expanded to others areas of North Yorkshire County Council, as it is seen as a good practice example of multi-agency problem-solving and a means to ensure that the best services are provided by a range of agencies to meet the needs of young people.

While there are many local examples of good practice in gathering and using data in non-statutory services, in reality even linking children’s social care data with early help data is not straightforward. There are several key issues that prevent a detailed analysis of support services, particularly when looking at multiple areas and services:

- Lack of uniformity in data sets: The original Cost Calculator tool for looked after children was built to utilise the SSDA903 (the DfE’s statutory looked after children data return). Although there are difficulties and limitations to utilising this data set (such as annual upgrades, changes to variables, and some local variance in data reporting), the standardised format enables a single tool to be used across areas.

However, in the absence of a generic ‘edge of care data return’ or any nationally agreed data framework being adopted by local services, there is not a single point of reference where analysts or researchers can begin their analyses. Instead, analysts are faced with the task of identifying multiple relevant indicators from available, routinely collected data, which will provide a limited view of some, but perhaps not all, of the edge of care cohort. - Variation in infrastructure: Local authorities use various management information and case management systems.3

- Real time or retrospective data: National data returns (such as the SSDA903 and the Children in Need Census) are produced annually and as such provide a retrospective picture. At a local level, their use in between the reporting timeframes is variable. They are therefore of limited use in ‘real time’ when analysing current caseloads and costings, and only provide a snapshot of local services. In order to generate the data necessary to ‘fuel’ an effective EoC CC, organisations would need to generate regular reports of the relevant child-level data which could be uploaded into the EoC CC as often as required for analysis and reporting.

Currently available data

Despite the variability between local approaches, it became increasingly evident throughout the project that many participating organisations had considered how best to utilise their data at a local level and were able to provide examples of local area data-linking and the matching of child-level data between agencies. So, although a single record of edge of care data might not exist, organisations are recording and analysing data related to young people who may be defined as edge of care, whether or not the organisation is providing a dedicated edge of care service.

The majority of local authorities had carried out additional secondary analyses of statutory Children in Need Census and SSDA903 data and had linked their child-level data with other multi-agency data. However, only around half the authorities tracked children between child in need and looked after systems, and only half linked child-level data with their finance systems.4

Whilst local analyses and data sets might currently vary too much to enable a wider analysis, the nationally reported data sets (made up of statutory data returns to Government departments) may assist in analysis at a macro level in the shorter term. The Change Project group agreed upon and discussed where data related to the edge of care cohort might already exist. Relevant data sets included:

- The SSDA903 return for looked after children

- The Children in Need Census

- The Schools Census

- The Troubled Families outcomes data

- Youth offending data

- NHS data.

The Change Project group agreed that the Edge of Care Cost Calculator tool should make use of these pre-existing data sets to create a child-level record that draws together key factors related to outcomes.

However, it was also acknowledged that none of these national data sets will exclusively include young people who are on the edge of care. Therefore, a more appropriate approach might be to: (1) filter cases based on definition criteria; and then (2) extract relevant data for each young person from across all data sets.

Finance data

Within this report we have summarised and assessed the availability and quality of data pertaining to the needs of young people on the edge of care, and also relevant outcomes data. The other key component of data necessary for a cost calculator tool relates to expenditure. Recent and current debates have focused on expenditure within Children’s Services (Thomas, 2018; Kelly et al, 2018) and, in particular, pressures on public sector budgets as a consequence of austerity and increased demand for Children’s Services. Spend by local authorities is reported annually and is broken down by services for looked after children, child protection and safeguarding/family support, as per the categories defined for the purposes of reporting.[5]

Previous research has highlighted the limitations of children’s social care expenditure data (Beecham and Sinclair, 2007; Ward et al, 2008; Holmes and McDermid, 2012). The expenditure returns provide data for a very specific purpose and can facilitate ‘top-down’ estimates of unit costs, when expenditure figures are divided by the number of children (and/ or families) who receive the service. A further limitation of organisations’ finance data and systems is that they are often not linked to data about children and families. Yet in order to understand the value of any service or intervention, it is necessary to ascertain who has received the service and link this data to information about needs, circumstances and outcomes.

The original Cost Calculator for Children’s Services (the CCfCS) utilises ‘bottom-up’ unit costs based on activity data about the amount of time spent on specific activities, such as an assessment or a review. The advantage of this approach to facilitate an exploration and explanation of cost variations has been well documented (Beecham, 2000; Beecham and Sinclair, 2007).

There was a clear appetite from participating organisations within this project to be able to understand variations in costs, and for these to be linked to needs and outcomes. The sessions also included discussions about the impact of austerity budgets on early help services and the concomitant increased demands on statutory children’s social care.

Costs of support

Throughout this report we have made reference to ‘bottom-up’ unit costs, whereby time-use data for different activities carried out by children’s social care personnel are estimated and translated into unit costs (see Beecham, 2000; Ward et al, 2008; Holmes and McDermid, 2012).

To move towards a ‘bottom-up’ unit costing approach for integration into the EoC CC, existing time-use data from previous research (Holmes and McDermid) were shared with the groups. The consensus was that these figures provide a useful starting point to understand time spent and costs associated with the support offered to all Children in Need (CiN), those who are the subject of a child protection plan and children looked after. The corresponding processes for Children in Need are detailed below.

Child in Need social care processes

| Process CiN 1

(includes no further action variation) |

Initial contact and referral |

|---|---|

|

Process CiN 2 |

Single assessment |

|

Process CiN 3 |

Ongoing provision (per month) |

|

Process CiN 4 |

Close case |

|

Process CiN 5 |

Section 47 enquiry |

|

Process CiN 6 (includes child protection variation) |

Planning and review: CiN |

|

Process CiN 7 |

Public Law Outline |

5 Section 251 of the Apprenticeships, Skills, Children and Learning Act 2009 requires local authorities to submit statements about their planned and actual expenditure on education and social care.

How data might be used to define the edge of care cohort

As per the earlier discussion, defining edge of care cohorts should combine service-led intelligence and data-led information. So a local area’s edge of care population might be defined as:

- All those identified by the local edge of care service(s), and

- All those identified by professionals as at risk of entering care and/or meeting eligibility criteria for local edge of care services

- All those identified by a set of evidence-informed criteria applied to local data sets.

Given the availability of several uniform data sets that contain relevant information, the EoC CC might be used to assist in a more generic identification of an edge of care population. As well as enabling benchmarking and analyses across multiple services, this may also enable organisations to identify young people at higher risk of entering care but who are not yet ‘on the radar’ of local services.

During the early stages of this Change Project, we asked local authorities to consider a long list of factors available from routine data sets which, when drawn together for analysis, might be used to help identify this population. The following draft list of key data indicators was agreed:

The child or young person:

- Is currently the subject of a child protection plan

- Meets the criteria for statutory services as a child in need

- Has recently left care

- Has been recorded as ‘missing’ recently

- Is currently in a foster placement

- Is absent from school more than 10 per cent of the time.

- Domestic violence incident(s) have been reported in the family/carer home.

- There are known to be substance misuse issues in the family or for the young person themselves.

The project group reached consensus that a combination of these risk factors was relevant, but that further investigation into exact thresholds for each factor was required. However, what this early exercise provided was a starting point for using readily available data to create a single definition of the edge of care population, based on agreeable data cut-off points.

Case study: Alternative identifications of the edge of care cohort

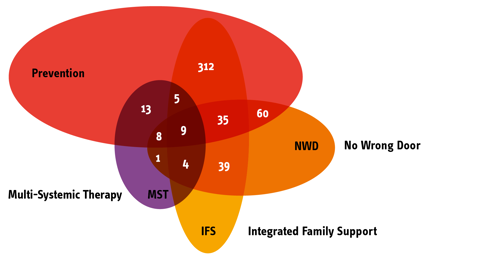

Some scoping work was conducted by one of the Change Project teams (from North Yorkshire) using the combination of approaches to defining the cohort, as discussed above:

Service-driven

This first exercise looked to identify young people who had been referred to prevention services and three different edge of care services in the county, and then to identify commonalities between these young people based on their data.

Of the referrals to prevention, 95 per cent did not get referred to an edge of care service and were dealt with by prevention services. Of the 5 per cent who were referred (542 young people), nine young people were subject to intervention by all three edge of care services (IFS, NWD and MST) and therefore deemed most at risk of becoming looked after.

It was interesting to note that these names, when shown to senior leadership at North Yorkshire, were not the names that the management would have anticipated being subject to all of this intervention activity, due to the specific nature of cases. This highlighted that even an exercise utilising only service-related definitions might identify cases that are going under the radar despite repeat referrals to edge of care services.

Data-driven

This exercise looked to identify those young people who had been in multiple edge of care services or who had moved between different risk registers. The analyst then excluded cases of young people currently in care and identified those who have been in care previously. They then looked at crossover between this edge of care population and markers from national data sets: child in need status, child protection, and child sexual exploitation (CSE) markers.

Of the 542 young people who had been in multiple edge of care services (5 per cent of total prevention cases), 488 were currently not in care and might be defined as ‘edge of care’ by service thresholds. Of these 488 young people, 71 (14.5 per cent) had been in care previously; 426 (87 per cent) were currently or had been a ‘child in need’; 163 (33 per cent) were or had been on a child protection plan; and 33 (7 per cent) had a CSE marker.

North Yorkshire were able to identify several cases which could be deemed ‘closer to the edge’ than others, based on their movement between multiple services and multiple risk factors. We also saw that some of these young people were not the expected ‘high-risk’ young people in the eyes of practitioners, highlighting the potential of a combined approach to identifying the cohort.

In the context of the EoC CC, clearly defined data thresholds could be used to filter whole data sets. Furthermore, using the balanced approach to defining the cohort suggested earlier in this report, it would be possible to compare outcomes between young people who are and are not receiving support from edge of care services.

The project group discussions enabled shared understanding and definition of the edge of care, sharing of practice, local context and desired outcomes, and the exploration of data related to edge of care services. This progress laid the foundations for the project team to begin the development of the EoC CC, which we will describe in the final section of this report.

The Edge of Care Cost Calculator tool

Purpose of the tool

The most appropriate conceptual framework and methodology for the EoC CC is one that is flexible and can include a variety of available relevant data. A fundamental component is to offer alternative approaches to the data inputs, whereby the model builds additional assumptions if certain data items are not available. It is these principles that underpin the current version of the original Cost Calculator for Children’s Services (CCfCS) for children in care.

An effective tool will serve two distinct purposes: (1) it will enable local services to evaluate their own provision; and (2) more widely, it will enable multi-area and national comparisons of services and benchmarking.

Data required

In the absence of a national edge of care data set, there are two options for the process of analysing edge of care data:

- Organisations complete a custom data entry document using data from their own internal systems.

- The tool utilises generic, statutory data returns and extracts relevant information.

Perhaps due to limitations on capacity and resources (and understandably so) the Change Project participants supported the option of a tool that uses currently available data sets with minimal need for adaptation. Discussions also focused on the use of supplementary child-level data (where it is available and can be linked by individual identifiers). This approach has been utilised for the development of the original CCfCS, essentially distinguishing between a ‘core’ set of data to provide meaningful analyses, and then supplementary data items.

Finance data

At a minimum, existing ‘top-down’ expenditure data can be used. These can subsequently be supplemented, or replaced by the research-based time-use data, as detailed above and/or additional finance information that exists in organisations.

Next steps

As detailed in this report, this Change Project enabled us to gather a wealth of information from the participants. It also highlighted the complexities associated with bringing together different types of data, variability in existing data, and differing perspectives about how the tool might be used.

To move forward, we plan to work in 2019 with a smaller group of Children’s Services organisations to test the pilot tool. This test and pilot phase will focus on the mechanisms for importing data and the tracking of cases between different parts of the children’s social care system (both in terms of ‘step up’ and ‘step down’).

This pilot phase will also focus on the development of new analyses, in the form of ‘dashboards’ that are informed by users, to inform strategic and operational planning at the local level.

Another aspect of the work that will be explored further is the applicability and usefulness of providing benchmarking data and analyses for comparisons between areas. Data for benchmarking purposes emerged as a key theme in this Change Project. However, given the complexities in terms of comparability of cohorts and data highlighted in this report, benchmarking would need further consideration and would require transparent caveats to avoid misinterpretation.

Conclusions

The scoping of both service provision and data collection undertaken for this Change Project provide valuable evidence for the onward development of the EoC CC. The practical insights of the Change Project group highlighted the level of flexibility needed for the EoC CC tool, and that further strategic thinking is needed around edge of care services to support sector-wide research.

In the real world landscape of a diversity of edge of care services and concomitant variance in available data, the key functions of an EoC CC tool are:

- To offer two modes of identifying the edge of care population (defined by local service, and defined by agreed data cut-off points).

- The option for services/local areas to adjust the tool’s thresholds to support their own internal analyses, plus default thresholds to support comparative analysis across local areas/services.

- To incorporate data from multiple sources, including the CiN Census, Schools Census, SSDA903, and Troubled Families data set, to assist with the identification of the cohort and to support more detailed outcomes mapping for those identified.

- This will need to create a single record for each child by using persistent identifiers to link multiple data sets together.

- Capacity built in to allow for the recording of outcomes from edge of care services.

- A template table might offer a flexible solution – where the user can input a shortlist of service outcomes for their own edge of care service.

- This may involve a change in internal monitoring systems, which might be at odds with current case management systems.

Beyond the development of the Edge of Care Cost Calculator tool, the Change Project posed several questions and highlighted areas that require further investigation:

- There is no agreed upon definition of the edge of care, and a common understanding would greatly assist further progress in this area. It is also worth bearing in mind that, since the term refers to young people and practice activity at the cusp of clearly demarcated statutory services, it may always be a somewhat nebulous concept.

- The field would benefit from a national service mapping exercise for edge of care services – summarising what is available, the population and referral criteria, and the intended outcomes.

- An additional piece of strategic work to help standardise edge of care recording and reporting across authorities – for instance, minimum requirements for data collection and a standard recording format.

- The sector should consider issues posed by the diversity in case management systems. It may be that some national development of case management would be more beneficial to good data practice.

Recommendations

Data

Edge of care services evolve in local contexts and in a competitive market for case management and information systems. This has led to a piecemeal environment for performance monitoring which poses challenges for independent research and for any benchmarking comparisons of edge of care provision. Further development of bespoke, local IT solutions may further challenge joined-up data processing and analysis.

Our recommendation is that a more effective and cost-effective way forward would involve a number of organisations pooling resources to develop a prototype standardised (but flexible) framework for gathering and analysing data. In the short term, there are some potential commonalities between local authorities that could be used to develop deeper service understanding at the edge of care.

Defining cohort/thresholds

While the Change Project focused on opportunities to improve the identification of children and young people on the edge of care using routine data sets, identification can never rely on data alone. Data sets cannot provide the narrative depth, evidence from direct observation, nuanced knowledge of family and community context, nor an understanding of the issues from the child or young person’s perspective. These are gained though good relationship-based practice and strong critical thinking and analysis. Nevertheless, there are clear gains to be made by supplementing human judgement with data-driven insight, and taking a balanced approach to defining the edge of care as highlighted in this report. To achieve this aspiration, using data available in all children’s services organisations and based on the practice experience of multiple edge of care service providers would represent a significant step forward in the use of data to support safeguarding and protection of children and young people.

References

-

Beecham J (2000) Unit costs: Not exactly child’s play. A guide to estimating unit costs for children’s social care. London: Department of Health, Dartington Social Research Unit, and Personal Social Services Research Unit, University of Kent.

-

Beecham J and Sinclair I (2007) Costs and outcomes in children’s social care: Messages from research. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

-

Bowyer S and Wilkinson J (2013) Models of adolescent care provision: Evidence scope. Dartington: Research in Practice.

-

Dixon J and Biehal N (2007) Young people on the edge of care: The use of respite placements. York: Social Work Research and Development Unit, University of York.

-

Dixon J, Lee J, Ellison S and Hicks L (2015) Supporting adolescents on the edge of care: The role of short term stays in residential care. An evidence scope. York: University of York.

-

Farmer E and Lutman E (2010) Case management and outcomes for neglected children returned to their parents: A five year follow-up study. (Research Brief DCSF-RB214). London: Department for Children, Schools and Families.

-

Holmes L (2014) ‘Estimating unit costs for Therapeutic Residential Care’ in Whittaker J, del Valle J and Holmes L (eds) Therapeutic Residential Care with children and youth: Developing evidence-based international practice. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

-

Holmes L and McDermid S (2012) Understanding costs and outcomes in child welfare services: A comprehensive costing approach to managing your resources. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

-

Institute of Public Care (2015) Hampshire County Council: Effective interventions and services for young people at the edge of care. Rapid research review. Oxford: IPC, Oxford Brookes University.

-

Kelly E, Lee T, Sibieta L and Waters T (2018) Public spending on children in England: 2000 to 2020. London: Children’s Commissioner for England.

-

Lushey C, Hyde-Dryden G, Holmes L and Blackmore J (2017) Evaluation of the No Wrong Door Innovation Programme: Research report. (Children’s Social Care Innovation Programme Evaluation Report 51.)

-

Ofsted (2011) Edging away from care: How services successfully prevent young people entering care. London: Ofsted.

-

Rees A, Luke N, Sebba J and McNeish D (2017) Adolescent service change and the edge of care. (Children’s Social Care Innovation Programme: Thematic report 2).

-

Thomas C (2018) Care Crisis Review: Factors contributing to national increases in numbers of looked after children and applications for care orders. London: Family Rights Group.

-

Wade J, Biehal N, Farrelly N and Sinclair I (2010) Maltreated children in the looked after system: A comparison of outcomes for those who go home and those who do not. (Research Brief DFE-RBX-10-06) London: Department for Education.

-

Ward H, Holmes L and Soper J (2008) Costs and consequences of placing children in care. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

-

Ward H, Brown R and Hyde-Dryden G (2014) Assessing parental capacity to change when children are on the edge of care: An overview of current research evidence. Research report. London: Department for Education.

-

Wickham H and Grolemund G (2016) R for data science: Import, tidy, transform, visualize, and model data. Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly Media.

-

Wilkinson J and Bowyer S (2017) The impacts of abuse and neglect on children; and comparison of different placement options: Evidence review. London: Department for Education.

Footnotes

-

This work built on previous research by Holmes and colleagues to develop a Cost Calculator for Children’s Services (CCfCS). Previous publications from this research provide detail about the development and use of the bottom-up unit costing methodology (see Holmes and McDermid, 2012; Ward et al, 2008).

-

Within our sample of 19 local authorities, seven different systems were reported: Capita One’s Integrated Children’s System (ICS), CoreLogic’s Frameworki, Servelec’s Mosaic, Servelec’s Synergy EIS, System C’s Liquidlogic, CareWorks’ RAISE, and Northgate’s e-Swift. Typically, a sub-section of data is extracted from these systems and converted into mandatory national data returns. At a local level, there is a lot of variation in how key information is recorded (such as how edge of care services are coded in finance data). As such, even if similar frameworks are being used, the exports from different information systems are unlikely to be similar enough to enable simple comparisons without significant ‘wrangling’ of the data.

-

Based on a sample of 14 of the 19 (74%) local authorities involved in the Change Project.

Professional Standards

PQS:KSS - Lead and govern excellent practice | Creating a context for excellent practice | Support effective decision-making | Quality assurance and improvement

PCF - Professionalism | Critical reflection and analysis | Contexts and organisations